|

reedom to operate or right-to-use is critical to a business. If someone else possesses patents that restrict your company’s right to make or use a product, your company has a significant risk. For that reason, freedom to operate analyses are often performed, preferably by a patent attorney. Freedom to operate can be examined at any time, but it is best to identify issues early on so, if necessary, product design changes can be made to eliminate or reduce the potential for liability. A time when at least a preliminary review of freedom to operate should be performed is when a patentability determination is made for new innovations. An analysis can determine whether the innovation is patentable as well as whether there are infringement risks or not. Of course, there are also other times when freedom to operate is examined. These may include simply becoming aware of a competitor’s patent or pending application, when concerns are expressed by a customer, or when moving into a new product area. Once we can identify potential infringement risks, we can assist in developing and implementing appropriate strategies to address these risks. One strategy may simply be acquiring a license if a license is available. Other strategies may include designing around or strategic patenting. Designing around and strategic patenting "Designing around" and "strategic patenting" are sometimes used interchangeably, but there are differences. Designing around refers to modifying a product or process to avoid infringement of someone else's patent. Sometimes one can protect the modifications with their own patent or patents. Strategic patenting, on the other hand, does not require the context of a particular product or process, but looks at existing patents and identifies improvements, changes, and patentable ideas of value in view of the existing patents. Here are some possible characteristics of strategic patenting:

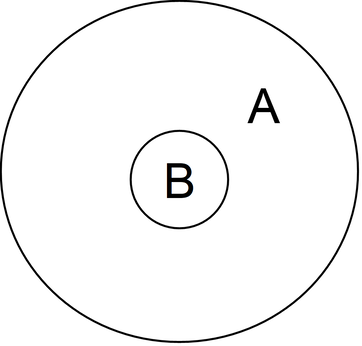

Sometimes using Venn diagrams provide some insight into the relationships that are helpful in strategic patenting.  To the left is one possible scenario. Where invention A is pre-existing, one can potentially patent invention B, which falls wholly within the scope defined by invention A, if invention B is patentable (i.e. novel and non-obvious) relative to A and other prior art. Since invention B falls wholly within the scope of A, invention B could not be practiced without infringing the patent for invention A. Invention A could be practiced without infringing the patent for invention B. Therefore, for the owner of B to gain advantage over A, invention B would need to be something that the owner of A would find of interest. This would be one instance where a patent may have narrow scope, but if its limitations are critical, the patent for invention B would have value. This example also emphasizes the point that strategic patenting is different from designing around. The owner of the patent for invention B does not have a right to practice their invention, thus, this scenario is no help for design around purposes, but it may still provide a benefit to the owner of the patent for invention B.

If you have freedom-to-operate questions or patent strategy questions, contact your GCO attorney or contact [email protected].

Comments are closed.

|

Postings provided here are provided by GCO attorneys or friends of GCO. If you have written a relevant blog post which you want published here, please contact [email protected]. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed